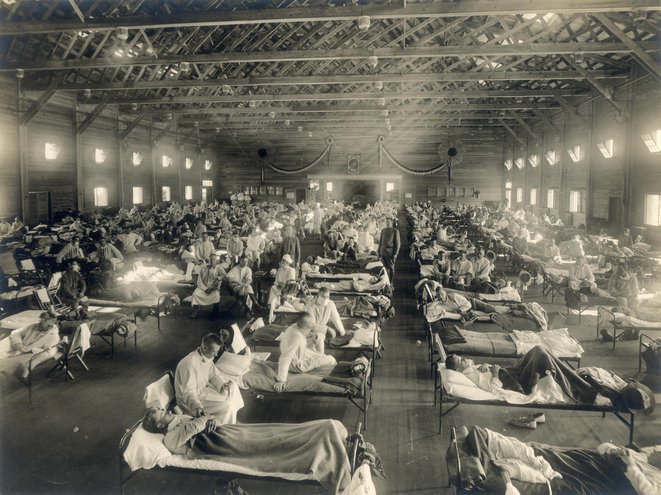

The construction of historical memories is not limited to the desire of highlighting critical events and give them a narrative structure; it is also done by selecting and by deleting memories which, for one reason or another, are perceived to be in conflict with that desire. The armistice itself was, at the time – unlike what happened on May 8, 1945 – a rather subdued celebration. There was a reason for this: the moment coincided with the tragic second wave of the influenza pandemic. The historiography of this pandemic is quite different from that of the two great wars in that it was not until the second half of the 1970s that it really began to attract the attention of historians. And it is only now, more than one hundred years later, that the general public is starting to understand how tragic it was. It was so obliterated from official records that it is now called the “forgotten pandemic”.

The 1917-1919 influenza pandemic is known as the “Spanish flu” not because it originated in Spain (which remained neutral during WWI) but because the Spanish press was not subjected to government censorship, unlike what happened in combatant countries. Therefore, the deadly outbreak in Spain became a recurring subject in the world press. It is now known that it originated in the US and was spread by American soldiers fighting in the European battlefields.

The governments of the combatant nations were by 1918 immensely discredited by the unnecessary horror of trench warfare. Fearing social upheaval and possible contagion of the Russian popular revolt against the Tsarist regime, they imposed widespread censorship on news relating to the flu pandemic that was by then rampant among the soldiers. The epidemic character of the pulmonary influenza was concealed and therefore preventive measures started to be implemented only when it was already completely out of control and spreading to the general population.

The flu pandemic claimed more victims than both world wars. It caused a drop in national GDPs equal to or greater than that of the First World War. The populations were so traumatized by the millions of deaths that it was partly responsible for the popular appeal of the various European authoritarian and dictatorial regimes which in the twenties and thirties advocated sanitary and hygienic ideologies that promised to build efficient state administrative systems in exchange for the loss of individual rights and freedoms.

The evocation of a memory is often done at the expense of deleting others. That is the reason why so many national authorities still vehemently celebrate Armistice Day: as a silent admission of guilt for their predecessors’ failure to manage the flu pandemic. When several government officials today speak of a “war against the coronavirus”, they are unconsciously re-constructing previous narratives, to make sense of what is, in fact, an absurdity: does the Coronavirus have a will and a conscience to understand that it is “an enemy” and that we are in a “state of war” against it? In insisting in this reductionist narrative, they (and we) are unfortunately obliterating other more meaningful possibilities of understanding the extraordinary events that we are experiencing globally.

We may, therefore, be facing a missed existential opportunity: that of considering the generalized pollution caused by the millions of tons of particulate matter that we humans produce daily as an “enemy that must be defeated”, “whatever the cost”.

TruePublica Editors Note – Air pollution in the UK is a major cause of diseases such as asthma, lung disease, stroke, and heart disease, and is estimated to cause forty thousand premature deaths each year, which is about 8.3% of deaths while costing the NHS around £40 billion each year. In 2017, research by the Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change and the Royal College of Physicians revealed that air pollution levels in 44 cities in the UK are above the recommended World Health Organization guidelines. The Royal College of Paediatricians, the Royal College of Physicians and Unicef have all made comment about unsafe air pollution and increased mortality associated with winter and influenza deaths.

Published in TruePublica, 14 April 2020

Publié à MediaPart, 11 Avril 2020

Publicat a L'Accent, 11 Abril 2020

Publicado n'O Público, 10 Abril 2020

RSS Feed

RSS Feed