THEMES IN ETHIOPIAN FOLK PAINTING

Christian Ethiopia is an African civilization whose preferred art form is not sculpture but painting. This art appropriated elements from Byzantine, Jewish, Arabic and Western styles. Many stylistic elements can be ascribed to the influence of early Christian missionaries coming to Ethiopia: the Aksumite ruler Ezana converted to the Christian faith as early as 4th century. Later, in the 6th century, Christianity spread over all Ethiopia by Syrian monks, the so-called “Nine Saints”. The missionaries, who preached a monotheistic orthodox faith, built a succession of churches and monasteries and translated the Bible into the local languages. As was customary in other Christian Orthodox churches, the artistic emphasis was on icons, fresco paintings and illuminations rather than on plastic representations (i.e. sculptures) of religious themes. This gave Ethiopian Christian art some of its characteristic features.

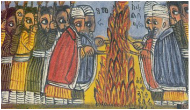

Not many artifacts have been left from the earliest period of Ethiopian art (6th – 16th century). Besides unfavourable climatic and economic conditions, the many wars and rebellions led to repeated great losses. The wars fought between the Muslim invaders led by Mohamed Grañ and the Christian northerners in the mid 16th century were particularly destructive and resulted in great loss and damage to Christian religious art. Most churches were burnt down and its art treasures were plundered and destroyed. His advances and willful destruction were eventually stopped with the help of Portuguese troops led by the last son of Vasco da Gama, Christopher, to whom the Ethiopian emperor Claudius (1540-1559) had called for military assistance.

The Roman-Catholic missionaries who accompanied the Portuguese troops soon exerted great influence on Ethiopian art. Of particular importance were the copies made from the painting of the Madonna from the Church of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, that were brought along by the missionaries, and that became the model for almost all later Ethiopian Madonna paintings, until the 20th century. It remained the ideal interpretation of the Madonna, even after Fasiladas (1632-1635) expelled the Jesuit missionaries from the country, and made Gondar the new capital of his kingdom, a function which the city retained until the founding of the present capital Addis Ababa in late 19th century. Another important painting was an Ecce Homo offered by king Manuel I of Portugal to the emperor Lebna Dengel: this painting was an item specially cherished by the Ethiopian emperors, until being taken to Great Britain by General Napier in the wake of the defeat and death of emperor Thewodoros, in late 19th century. Icons based on it are present in most Ethiopian churches.

Ethiopia has kept its Christian character up to the present time. In North and Central Ethiopia there are still hundreds of monasteries and churches from the Middle Ages that were spared destruction. They are decorated with paintings and frescos on themes of the Old and New Testament. As only a small part of the congregations could read, they received (and still receive) their religious instructions and information with the help of these church paintings. It should also be noted that mass services are to this day conducted in ge’ez, an ancient erudite language that very few people understand.

Ethiopian painters were obliged to go through a religious education and training process during which they not only learned their painting techniques and skills but also studied part of the syllabus required for priesthood. Quangeta Jembere Hailu, for instance, whose paintings became well-known in Europe from the 1940s onwards, was trained in the religious disciplines of Tsome Degwa, Qene, Zenare and Aquaquam which generally require up to 30 years study. Even if many artists received their technical skills from relatives or acquaintances (e.g. the painters from the Belachew family, well-known in Europe in the 1930s), they still needed to have thorough knowledge of the Old and New Testament in order to reproduce the scenes in their paintings. In earlier times, painting was strictly a man’s prerogative. The Orthodox Church forbade painting by women because women were considered ritually impure during menstruation. Church painters were not allowed to paint pictures with a secular theme, neither could they simply paint pictures for sale, being tied to a particular church or monastery. Their patrons were generally wealthy citizens and the aristocracy who demonstrated their gratitude to their church, by commanding ex votos to the painters. The early Ethiopian paintings of secular themes that reached Europe were actually ‘”clandestine”. The creation of collections in the West brought notoriety to some painters, who started signing their work. Even so, an important part of the painting production is still sold unsigned.

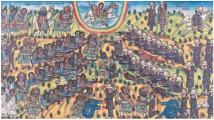

When Ethiopia won the war against Italy in 1896 she was granted diplomatic status by most European nations. The resultant influx of diplomats and their families who sought contact with the local artists, soon led to the development of Ethiopian folk painting because most preferred commissioning paintings on secular and not religious themes and liked to have their own portrait painted. Ethiopian paintings therefore began to arrive in Europe and were soon collected by various museums. The foundation of many a Ethiopian art collection was therefore laid in late 19th and beginning of 20th century. Some of the most popular motifs were hunting scenes, the legend of the Queen of Sheba, daily peasant life and battle scenes of the wars of 1868 (against Britain) and 1896 (against Italy) as well as the battles by the Ethiopians and Portuguese against Ahmed Grañ.

Paintings produced during the First World are missing in European and American collections because there was virtually no contact between Ethiopia and Europe. Only after about 1920 did collecting start again for a period that lasted until about 1940. In addition to the old motifs, paintings of these years show above all technical achievements newly introduced to Ethiopia (e.g. postal services, trains, cars and aeroplanes), as well as horse racing. Another important theme was Haile Selassie’s investiture as Emperor. After the Second World War, from about 1950, more tourists began to visit the country, which has and helped to turn folk lay painting into a flourishing art again. The artists in those days were particularly productive and created the so-called “airport art”, which was specifically tailored to the tourists’ preferences and need for smaller sized pictures (to prevent transport problems). It also became more common to use skins instead of canvas as painting surfaces.

“Classic folk painting” disappeared between 1974 and 1990. During the Communist rule religious themes were frowned upon and tourists were no longer around to buy paintings, which meant that painters lost an important means of earning a living. There were hardly any successors, and by and by the art of folk painting almost died out when many of the old practising painters died. There were some artists, however, who turned to Communist propaganda art for which there was ample demand. They drew huge posters of Marx, Engels, and other representatives of the Communist ideology that were then displayed in official buildings or in market squares.

The Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), who presently governs the country, also uses folk painting as an instrument to promote its ideas and messages. After the fall of the Communist military regime, the exiled dictator Mengistu Halie Maryam and the heads of the old regime, were painted like devils with horns and displayed on large hoardings. Indeed, they are meant to look despicable and despised like despots and brutal successors of Hitler or Stalin.

The pictures in this exhibition illustrate some of the characteristics of Ethiopian folk painting. Before detailing the most common themes, some basic points need to be explained:

The painters generally do without ‘unnecessary’ background such as landscapes, plants, animals or buildings and concentrate on the illustration of the religious or lay theme. Their technique requires them to draw the outlines of the figures in black first, and then to paint the spaces in clear, strong, brilliant colours. After that the final contours are redrawn in black. No attention is paid to light and shade, perspectives or life-like actions. On the contrary, the stiff posture of the people is a reminder of the tradition of religious painting, in which an hieratic posture indicates that they are sacred and required great “dignity” in their depiction. In this connection it is worth mentioning that Christ was often portrayed with the typical features of an Ethiopian ruler, and always with fair complexion.

Rulers and people of noble birth always had to be tall and given a very fair complexion, no matter how dark and small they were in real life. The same applied to saints and archangels, who were always very light skinned, with long beards and without any shadows on their faces. Often, they were represented on horseback and always wearing a cloak. Being sheltered under an umbrella was equally a sign of high status, because only members of the royal family, dignitaries and priests were allowed to use an umbrella. Servants, on the other hand, were painted dark or grey, and small. The Devil in Ethiopian painting is painted as black, grey or very dark blue skinned and usually naked.

Other typical features of Ethiopian paintings are that good people are shown with two overlarge eyes, whereas unbelievers or enemies are only seen in profile with one eye. The large hands, most often seen in paintings of the Madonna, signify generosity and an all-embracing love.

The pictures were, and still are, generally painted on canvas (panels and painted folk ”stories”), parchment (illuminations and painted folk “stories”), wood (icons) or bare rock surface (frescos). Paper or cardboard was used only after t’edj-bet paintings (paintings used to decorate bars and restaurants) became fashionable in 20th century. The secret of the right mixture of tempera colours (home-made colours that have kept their brilliance for many centuries), which was generally passed orally from master to student, lost its importance when ready mixed imported colours were introduced in Ethiopian painting during 19th century.

Not many artifacts have been left from the earliest period of Ethiopian art (6th – 16th century). Besides unfavourable climatic and economic conditions, the many wars and rebellions led to repeated great losses. The wars fought between the Muslim invaders led by Mohamed Grañ and the Christian northerners in the mid 16th century were particularly destructive and resulted in great loss and damage to Christian religious art. Most churches were burnt down and its art treasures were plundered and destroyed. His advances and willful destruction were eventually stopped with the help of Portuguese troops led by the last son of Vasco da Gama, Christopher, to whom the Ethiopian emperor Claudius (1540-1559) had called for military assistance.

The Roman-Catholic missionaries who accompanied the Portuguese troops soon exerted great influence on Ethiopian art. Of particular importance were the copies made from the painting of the Madonna from the Church of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, that were brought along by the missionaries, and that became the model for almost all later Ethiopian Madonna paintings, until the 20th century. It remained the ideal interpretation of the Madonna, even after Fasiladas (1632-1635) expelled the Jesuit missionaries from the country, and made Gondar the new capital of his kingdom, a function which the city retained until the founding of the present capital Addis Ababa in late 19th century. Another important painting was an Ecce Homo offered by king Manuel I of Portugal to the emperor Lebna Dengel: this painting was an item specially cherished by the Ethiopian emperors, until being taken to Great Britain by General Napier in the wake of the defeat and death of emperor Thewodoros, in late 19th century. Icons based on it are present in most Ethiopian churches.

Ethiopia has kept its Christian character up to the present time. In North and Central Ethiopia there are still hundreds of monasteries and churches from the Middle Ages that were spared destruction. They are decorated with paintings and frescos on themes of the Old and New Testament. As only a small part of the congregations could read, they received (and still receive) their religious instructions and information with the help of these church paintings. It should also be noted that mass services are to this day conducted in ge’ez, an ancient erudite language that very few people understand.

Ethiopian painters were obliged to go through a religious education and training process during which they not only learned their painting techniques and skills but also studied part of the syllabus required for priesthood. Quangeta Jembere Hailu, for instance, whose paintings became well-known in Europe from the 1940s onwards, was trained in the religious disciplines of Tsome Degwa, Qene, Zenare and Aquaquam which generally require up to 30 years study. Even if many artists received their technical skills from relatives or acquaintances (e.g. the painters from the Belachew family, well-known in Europe in the 1930s), they still needed to have thorough knowledge of the Old and New Testament in order to reproduce the scenes in their paintings. In earlier times, painting was strictly a man’s prerogative. The Orthodox Church forbade painting by women because women were considered ritually impure during menstruation. Church painters were not allowed to paint pictures with a secular theme, neither could they simply paint pictures for sale, being tied to a particular church or monastery. Their patrons were generally wealthy citizens and the aristocracy who demonstrated their gratitude to their church, by commanding ex votos to the painters. The early Ethiopian paintings of secular themes that reached Europe were actually ‘”clandestine”. The creation of collections in the West brought notoriety to some painters, who started signing their work. Even so, an important part of the painting production is still sold unsigned.

When Ethiopia won the war against Italy in 1896 she was granted diplomatic status by most European nations. The resultant influx of diplomats and their families who sought contact with the local artists, soon led to the development of Ethiopian folk painting because most preferred commissioning paintings on secular and not religious themes and liked to have their own portrait painted. Ethiopian paintings therefore began to arrive in Europe and were soon collected by various museums. The foundation of many a Ethiopian art collection was therefore laid in late 19th and beginning of 20th century. Some of the most popular motifs were hunting scenes, the legend of the Queen of Sheba, daily peasant life and battle scenes of the wars of 1868 (against Britain) and 1896 (against Italy) as well as the battles by the Ethiopians and Portuguese against Ahmed Grañ.

Paintings produced during the First World are missing in European and American collections because there was virtually no contact between Ethiopia and Europe. Only after about 1920 did collecting start again for a period that lasted until about 1940. In addition to the old motifs, paintings of these years show above all technical achievements newly introduced to Ethiopia (e.g. postal services, trains, cars and aeroplanes), as well as horse racing. Another important theme was Haile Selassie’s investiture as Emperor. After the Second World War, from about 1950, more tourists began to visit the country, which has and helped to turn folk lay painting into a flourishing art again. The artists in those days were particularly productive and created the so-called “airport art”, which was specifically tailored to the tourists’ preferences and need for smaller sized pictures (to prevent transport problems). It also became more common to use skins instead of canvas as painting surfaces.

“Classic folk painting” disappeared between 1974 and 1990. During the Communist rule religious themes were frowned upon and tourists were no longer around to buy paintings, which meant that painters lost an important means of earning a living. There were hardly any successors, and by and by the art of folk painting almost died out when many of the old practising painters died. There were some artists, however, who turned to Communist propaganda art for which there was ample demand. They drew huge posters of Marx, Engels, and other representatives of the Communist ideology that were then displayed in official buildings or in market squares.

The Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), who presently governs the country, also uses folk painting as an instrument to promote its ideas and messages. After the fall of the Communist military regime, the exiled dictator Mengistu Halie Maryam and the heads of the old regime, were painted like devils with horns and displayed on large hoardings. Indeed, they are meant to look despicable and despised like despots and brutal successors of Hitler or Stalin.

The pictures in this exhibition illustrate some of the characteristics of Ethiopian folk painting. Before detailing the most common themes, some basic points need to be explained:

The painters generally do without ‘unnecessary’ background such as landscapes, plants, animals or buildings and concentrate on the illustration of the religious or lay theme. Their technique requires them to draw the outlines of the figures in black first, and then to paint the spaces in clear, strong, brilliant colours. After that the final contours are redrawn in black. No attention is paid to light and shade, perspectives or life-like actions. On the contrary, the stiff posture of the people is a reminder of the tradition of religious painting, in which an hieratic posture indicates that they are sacred and required great “dignity” in their depiction. In this connection it is worth mentioning that Christ was often portrayed with the typical features of an Ethiopian ruler, and always with fair complexion.

Rulers and people of noble birth always had to be tall and given a very fair complexion, no matter how dark and small they were in real life. The same applied to saints and archangels, who were always very light skinned, with long beards and without any shadows on their faces. Often, they were represented on horseback and always wearing a cloak. Being sheltered under an umbrella was equally a sign of high status, because only members of the royal family, dignitaries and priests were allowed to use an umbrella. Servants, on the other hand, were painted dark or grey, and small. The Devil in Ethiopian painting is painted as black, grey or very dark blue skinned and usually naked.

Other typical features of Ethiopian paintings are that good people are shown with two overlarge eyes, whereas unbelievers or enemies are only seen in profile with one eye. The large hands, most often seen in paintings of the Madonna, signify generosity and an all-embracing love.

The pictures were, and still are, generally painted on canvas (panels and painted folk ”stories”), parchment (illuminations and painted folk “stories”), wood (icons) or bare rock surface (frescos). Paper or cardboard was used only after t’edj-bet paintings (paintings used to decorate bars and restaurants) became fashionable in 20th century. The secret of the right mixture of tempera colours (home-made colours that have kept their brilliance for many centuries), which was generally passed orally from master to student, lost its importance when ready mixed imported colours were introduced in Ethiopian painting during 19th century.