THE INDIGENOUS & THE FOREIGN

Jesuit Presence in 17th Century Ethiopia

STONE ARCHITECTURE IN 17TH CENTURY ETHIOPIA

|

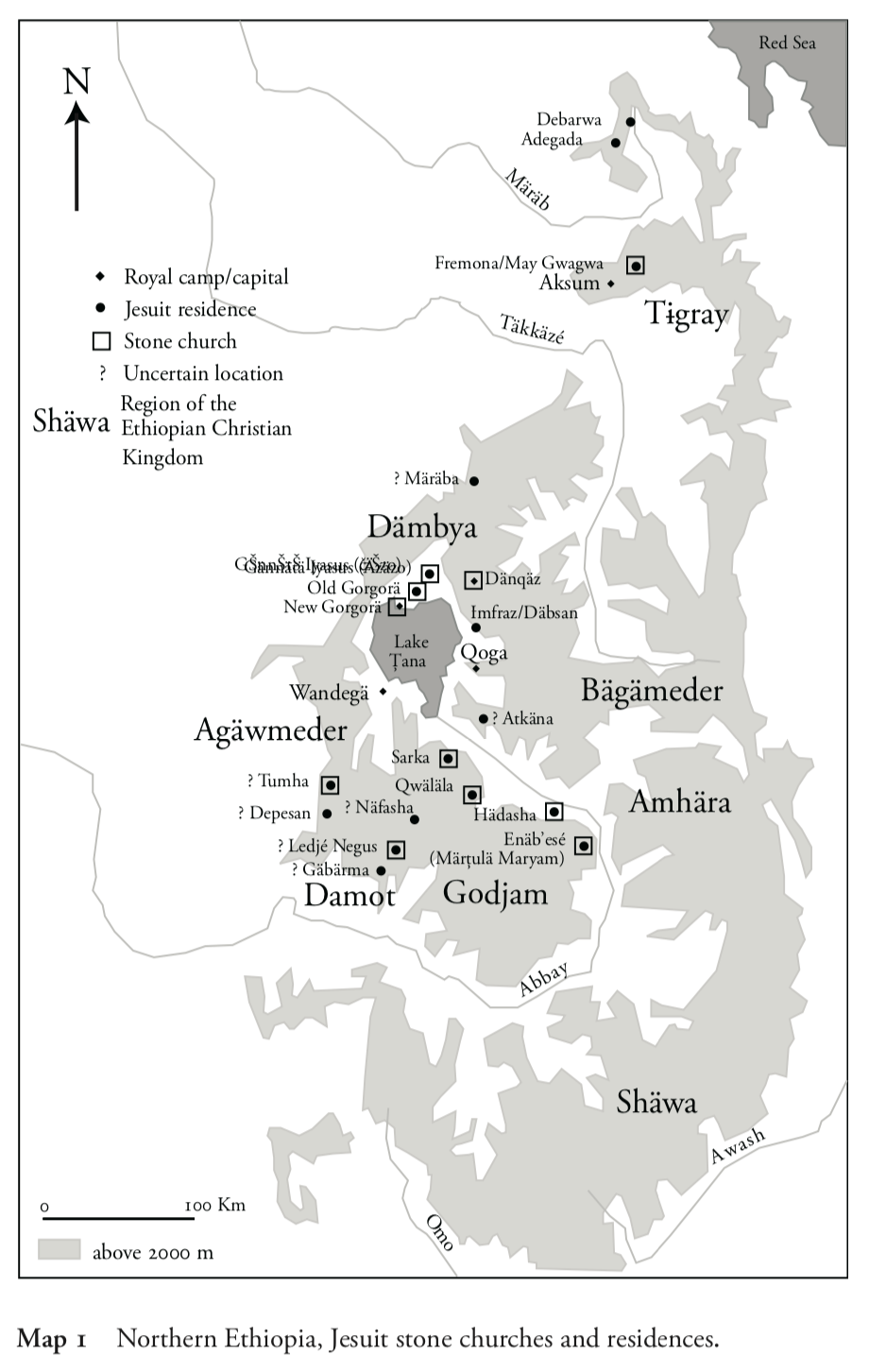

According to the legend of the foundation of Gondar by King Fasiladas, an old prophecy said that a new era for Ethiopian Christianity would begin once a righteous king had permanently established his royal court in a place with a name bearing the letter G. By trial and error, the predecessors of Fasiladas built stone castles in Gorgora, Gomange, Guzara and Gannata Iyasus. This legendary prophecy indicates, after the fact, how the concept of the royal camp as a political and cosmological centre and, more generally, the concept of urban life in Ethiopia changed so deeply with the replacement of semi-itinerant royal tents with castles built of stone and mortar. It also stresses the existence of an historical and structural connection between Gondar and the pre-Gondarine royal compounds. The first castles were built in Dambya and Gojam, after the establishment of a Portuguese community in the highlands (after 1543), and the occupation of the Eritrean coast by a Turkish force (in 1557). From site to site, the royal residences follow this same general architectural pattern: quadrangular castles in stone and mortar, with adjacent cisterns to maintain a permanent water supply, surrounded by roughly circular walled compounds surmounted by cylindrical towers with egg-shaped tops. A more systematic discussion of the origin of the pre-Gondarine and Gondarine castles is still awaiting a comparative analysis of architectural typologies and building procedures. Scholars have suggested that Portuguese and/or Turkish defensive architecture may have been particularly influential. For instance, the central tower of the castle of Fasiladas in Gondar is reminiscent of the telescopic towers of early 16thcentury Portuguese military architecture. A rather different influence can be detected in the leisure pavilion in the centre of the basin at Azazo. It seems to have been inspired in Indian palace architecture: according to Father Manuel de Almeida, a piping system raised water to the roof, from which it fell as a screen, refreshing the pavilion. It is relatively easy to trace the design of the 17th-century Catholic churches and residences in Ethiopia to the Jesuit missionaries arriving from Southern Europe, via Goa in India. Building in stone and mortar required technical knowledge, tools, and suitable stone for cutting into blocks and for carving, as well as limestone or shells to prepare mortar. It also required qualified masons, carpenters and plasterers. All this was made possible through the exchange of craftsmanship between Ethiopians, Turks, Indians and Portuguese. To build the churches, the priests relied on two alternative plans that had been developed by the Society of Jesus in Europe to be adopted in their missions all over the world: - the “hall church” (as in New Gorgora and Azazo), which responded to a congregational idea of the religious community; - the Latin cross-shaped church, in which the inner space was organized according to the very strict ritual rules codified at Trent and was well lit by large windows (the cathedral of Dankaz followed the same plan as the that of the Roman Church of Jesus, by the architect Vignola). The plain architecture favoured the decoration of the inner walls and arches, as in Martula Maryam. The Catholic patriarch’s house in Dabsan, built in at least three different stages, is a particularly interesting example of the mix of building techniques tried by the masons that worked for the Jesuit missionaries. |

|